By Corey Bingaman, Western Oregon Field Coordinator for the American Forest Resource Council

Fuel reduction projects are often maligned by those who oppose active forest management. Critics point to the fact that, during certain conditions, no amount of fuels reduction will stop large fires from burning out of control. Although evidence suggests that fuels-reduction projects and timber sales can have a moderating effect on fire behavior during even the largest conflagrations; it is true that when conditions become extreme, a 200-foot fuel break will have little ability to “stop” a fire.

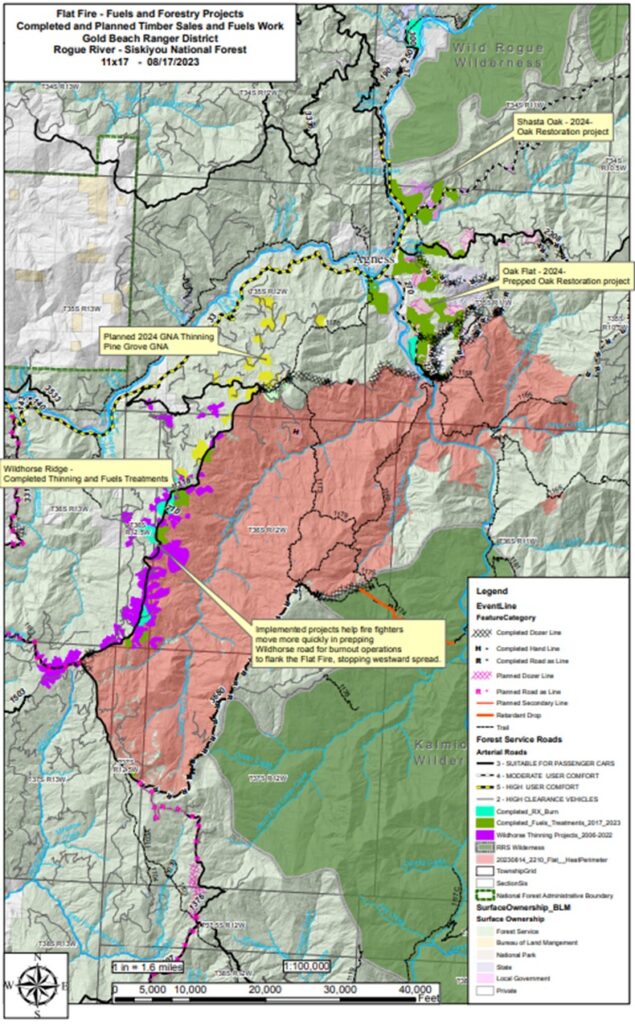

Where anti-forestry groups miss the mark on fuel reduction projects is in judging their effectiveness where it counts – during active firing operations. Such is the case on the Rogue-Siskiyou National Forest, where years of fuel reduction work and strategic timber sales have given firefighting personnel a leg-up in their effort to control the 2023 Flat Fire.

The Flat Fire started on July 15, 2023 in the Oak Flat Campground near the town of Agness, Oregon. Strong winds, hot and dry conditions, and an abundance of snags and brush leftover from the 2002 Biscuit Fire, enabled early growth on the Flat Fire. Within a week over 20,000 acres had burned and there was a real threat that the fire could push into Agness or Gold Beach if left un-checked. Snags not only provided easily combustible fuel for the fire, but they also complicate firefighting efforts as crews cannot mobilize where the risk of overhead hazards are too high. Simply-put: due to the fuel loads, the forecasted weather, proximity to communities, and the occurrence of the fire so early in the season, the Flat Fire threatened to become an historic conflagration.

Fortunately, the Flat Fire started near a ridgeline that the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest had long identified as a critical control point within their boundary. Wildhorse Ridge begins above the confluence of the Rogue and Illinois Rivers near Agness and extends south for about 19 miles, before terminating near the confluence of the Pistol and North Fork Pistol Rivers. As a strategic control point, Wildhorse Ridge is the first line of defense between fires coming out of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness and the town of Gold Beach.

The importance of Wildhorse Ridge played out in 2002 during the Biscuit Fire, where crews were able to contain the fire’s westward advance along Wildhorse Ridge, thus preventing continued destruction of public and private resources during what was (at the time) the largest wildfire in State history. Although much of the forested area between the Kalmiopsis Wilderness and Wildhorse Ridge had burned completely during the Biscuit Fire, many green islands of lightly burned timber remained.

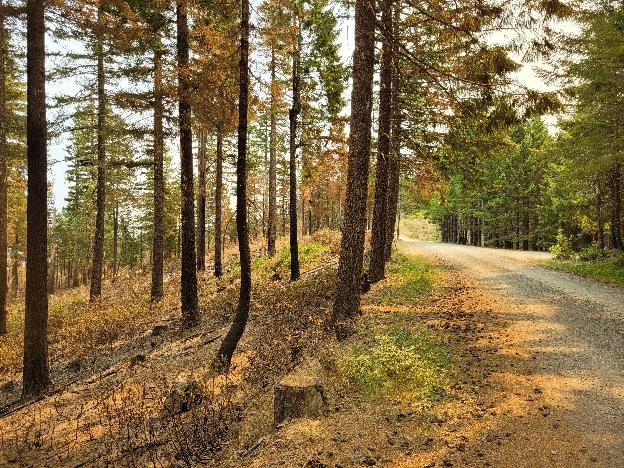

Following the Biscuit Fire, the strategic importance of Wildhorse Ridge was increased as it now not only protected Gold Beach, but also an immense swath of unburned timberland of mixed public and private ownership. To bolster the ridgeline’s defense, and to impart greater resilience within the moderately-burned green islands, the Forest began a series of timber sales and fuels reduction projects along this ridgeline starting in 2006. The aim of these projects varied from non-commercial fuels-reductions to conventional timber sales via commercial thinning. These projects were also designed to ensure that that roads across the ridge remained in drivable condition in the event of necessary emergency response.

The effectiveness of these projects was tested this summer during the early days of the Flat Fire, and it didn’t take long before the value of these treatments became clear. As the fire broke out, firefighting personnel were able to utilize the roadway to quickly gain access to the fire’s origin and establish an anchor point, preventing spread towards Agness. As the fire progressed south, Wildhorse Ridge became an invaluable resource to move personnel in and out safely. Treatments along the ridge made it possible for firefighters to safely backfire into the main fire and eliminate flashier fuels between the main fire and the ridge without the risk of putting fire into overgrown fuels.

The Forest was also able to take advantage of some breaks along the way. The 2018 Klondike fire afforded the Forest the opportunity to reopen containment lines along the fire’s eastern front, and weather moderated at pivotal points to allow firefighters to gain ground on the fire. But while good fortune can be a saving grace during fire season, nothing compares to hard work and preparation. The Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest was well-prepared to utilize Wildhorse Ridge during the Flat Fire because of their own hard work.

It’s still too early to predict the final impacts of the 2023 Flat Fire. The fire continues to burn, and there is no end in sight for the year’s fire season. But as of August 28, the Flat Fire is 34,242 acres, 58% contained and has grown very little in the past few weeks. This comes as a welcome relief as the Forest must divert resources to their Wild Rivers Ranger District, where the Six Rivers Complex along the OR/CA border continues to advance into the State.

If the Rogue River-Siskiyou can hold the fire in place through the season, the Forest should be a model for federal land managers who have been tasked with preparing their forests to withstand the effects of unprecedented global climate change. Fortune favors those who are willing to work for it.